The characters on Six Feet Under are contending with the biggest questions we have: Why am I here? What’s the point of life? Of death? Am I a good person? Do I know how to love?

Their internal and outward struggles ground the plot in existential matters of authenticity, meaning, isolation, freedom, and death anxiety. So just for fun I’m breaking down, existential therapy wise, the main characters’ struggles. In the first article in this series, I talked about isolation. Today I’m talking about Nate Fisher’s existential crisis of authenticity.

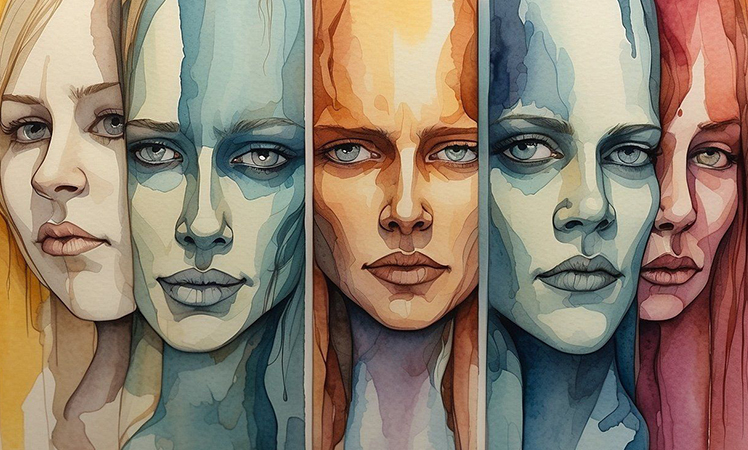

An identity crisis

Existential therapy approaches questions about identity through the idea of authenticity, an ongoing process of accepting the reality of your existence and taking responsibility for making something of it. Identity is what makes you you and not any other person: your experiences and memories, the interpersonal roles you take on, your social locations, your desires and interests, your choices and actions, your values.

We ask ourselves about authenticity all the time:

What do I want?

Am I a good person?

What should I do?

Who am I, really?

Finding your own answers and learning how to reflect those in your choices helps you move through the world in a state that accurately reflects what makes you you. This moves you beyond merely acting out your conditioning or performative roles. Identity is something continually defined through authentic, consistent action; it can remain constant, and it can change.

Nate, the eldest son of a funeral director, is in a constant identity crisis throughout Six Feet Under. He has drifted through life relying on his privilege, looks, and charm, rather than any self-directed choices. In the opening episode, Nate sums up his life to date:

“I live in a shitty apartment which was supposed to be temporary. I work at a job which was also supposed to be temporary, until I figured out what I really wanted to do with my life, which is apparently nothing. I have lots of sex but haven’t had a relationship last more than a couple of months. … I’m going to be one of those losers who ends up on his deathbed saying, where did my life go?” (season 1, episode 1)

Nate says this to his sister as they are both coping with the immediate aftermath of their father’s death in a car accident. After this first episode, Nate quickly finds himself both living back at home and deciding to be a funeral director after all, a role he has resisted his entire life, simply because his father left half the business to him in the will.

This characterizes Nate’s existence: being thrown into situations and going with it because that’s the path of least resistance. He’s exerted very little active will in defining who he is. And that’s why he spends 5 seasons wrestling with authenticity.

The connection between authenticity and freedom

Nate’s crisis seemingly starts to resolve when he chooses to take on the family business, but is this a resolution or a deferral? A few episodes later, he wonders if he made the choice for all the wrong reasons (to satisfy his mother, because his father ordained it). And he spends much of the rest of the show grappling with this choice and what it means for his identity.

Being thrown into unexpected situations is part of life. Existentialists talk about this “thrownness,” which starts with our birth into family, community, culture, and sociopolitical conditions we did not choose. We can do what Nate does, which is look everywhere for guidance but within—handing our agency to others—or we can recognize our freedom to choose how to interact with the contexts we are thrown into.

Deciding to be a funeral director helps Nate start to think that perhaps he is a good person, because he’s doing good work. Finding self-worth in the work we choose can move us closer to an authentic life, if that work takes on true meaning for us. But this budding comfort is thrown to the wind in season 2, when he finds out he’s accidentally gotten an old friend pregnant and can’t manage to tell the truth to his fiancée. That relationship implodes when he finally comes clean, unsurprisingly. Shortly after, Nate finds out he has to undergo brain surgery.

As you can imagine, facing death brings up these existential authenticity questions all over again (Who am I? What do I want? Am I a good person?).

Self-deception

Fast forward to the next season, and we find out Nate decided to marry Lisa, the friend, and be a father to their child. Nate again uses this opportunity to try to answer one of those questions: yes, I can be a good person by showing up for this child and her mother. His commitment to fatherhood is clear, as is his commitment to trying to be a good partner. It’s just as clear that he’s miserable in the relationship. He is working against his true desire to attempt to give Lisa what she wants and stabilize his identity as a good person.

Nate’s way of contending with his identity is an example of what the existentialist philosopher Jean-Luc Sartre called bad faith, a form of self-deception by which we deny our inherent right to choose our actions and path. Nate becomes a funeral director because of his father’s expectation, a husband because of his friend’s expectation, a father because of his family’s and society’s expectations. He is living in three roles, none of which he’s chosen for himself but all of which he works to perform well. But a performance is not the same as an authentic movement to claim responsibility for his choices and what they reflect about who he is.

And the consequence is severe. While catching up with his former fiancée over lunch, Nate explains:

“You just have to work at it, every day. Can’t expect everything to be perfect all the time. And if there’s a moment when I feel like I’m in prison, I just have to think about all those moments when it feels safe. And remind myself that those moments outweigh the prison moments.” (season 3, episode 5)

Trading an occasional feeling of safety for “moments when I feel like I’m in prison?” No thank you.

When giving up freedom means giving up authenticity

Allen Wheelis talks about trading freedom for safety in How People Change. He speaks of freedom and necessity as opposing forces we use to make, and justify, our choices. Nate feels compelled by arbitrary necessity to function as a family man, but he was free to choose otherwise. He is aware he’s given up his freedom, but has done so to reduce internal conflict and tension.

Tension reduction is not necessarily a good thing, though. He’s traded his own agency and pursuit of joy to avoid the inherent anxiety of choosing his own life. Existentialism proposes that having freedom inevitably comes with anxiety. On the whole, that anxiety is actually a good thing for us. It drives us forward and motivates us to find the authentic path.

At this point, Nate is on his way to becoming much like his father, because he postponed identity development. Nate rebelled as a teen and took off as soon as he could to avoid this very outcome. But rather than progressing beyond this defining against—which is still a defining by—he avoided cultivating himself. And he ends up exactly right where he started: in a prison of inauthenticity.

Later on in season 3, Nate’s wife Lisa dies, freeing him from the marriage. But Nate never finds resolution around this crisis. He repeats the cycle with his fiancée from season 1—marriage, parenthood—and finds himself unhappy again. He decides to leave her for someone else just before he dies from a complication from his brain surgery near the end of season 5.

One quirky feature of Six Feet Under, which is set in a funeral home, is that those who have died are still around for those who are living to talk to. At the end of season 5, Nate’s sister Claire is sitting in the park where he was buried, talking to him. She’s lamenting the state of her own aimless life. He says, “You want to know a secret? I spent my whole life being scared, scared of not being ready, of not being right, of not being who I should be. And where did it get me?” (emphasis mine; season 5, episode 12)

I can’t wrap the article up any better than that.